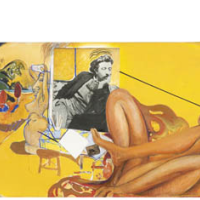

BRETT WHITELEY, Gauguin 1968

This painting has never been seen in Australia. Brett Whiteley created his Gauguin at the Chelsea Hotel in New York in 1968 and it has remained there until this time.

The famous American playwright Arthur Miller remained secluded at The Chelsea for six years after the breakup of his marriage to Marilyn Monroe. His observations of the Lower Manhattan hotel are typically insightful:

The Chelsea in the Sixties seemed to combine two atmospheres: a scary optimistic chaos, which predicted the hip future and at the same time the feel of a massive, old-fashioned, sheltering family… The idea of family had limits… unless one was drugged out, or spending one’s days putting paint on canvas, words on paper, chisels on stone, or singing operatic arias at the piano, … You could get high in the elevators on the residue of marijuana smoke. … The Chelsea, whatever else it was, was a house of infinite toleration.1

In short, it was a cultural magnet. Its pull was strong enough to, at various times, draw Dylan Thomas, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Frida Kahlo, Jasper Johns, Kenneth Tynan, Allen Ginsburg, Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious, Arthur C. Clarke, Madonna and, of course, Brett Whiteley.

In other words, in the Sixties, it was the place to be or to have been. By the time that Whiteley, on a Harkness Fellowship, arrived (1967) to live in The Chelsea’s penthouse the creative wave had all but rolled on. However, there was enough surge left in the old dowager hotel’s artistic ambience to propel his own creative impulses.2

Infused with an almost messianic fervour Whiteley embarked upon a small number of highly dramatic paintings, compressed within an equally dramatic two-year period, that represent a remarkably forceful departure from the style of his earlier London-based works.

Whiteley was on fire! He had entered a blazing period of self-reflexive intensity and his contemporaneous paintings fervently displayed the results of an expansive vision that was peopled with emblematic portraits, peppered with collages and piled with sociological references.

The most operatic of these thought-provoking New York paintings is his encyclopaedically dense twenty-two metre long polyptych entitled The American Dream of 1969, now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, which seems to encapsulate the panoramic neon-lit societal scope of James Rosenquist (1933-) as well as reflect the contemporary angst and urgency to be found in the brooding socio-aesthetically fractured paintings of Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008).3

In New York, Whiteley’s painting style became less calligraphic and more sweeping; his compositions there embraced crescent-shaped expanses and traversed even larger areas of physical and mental space; his colours became more vibrant and his highly diverse use of collage mirrored both literary and social sources almost with abandon.

The artistic results are both filmic in scope and vivid in their impact. One does not just look at these extraordinary paintings – one swoons in front of them. Their sense of enveloping intensity is awe-inspiring.

One of the best of these rare and intense New York paintings is his Gauguin of 1968 – a large and uniquely shaped work that is almost languorously magisterial in its immediate and striking visual impact. Its left to right “laid-back” tumble of indicative forms moves from the vegetative through to the corporeal and on and upwards to the inorganic (the uppermost bottle of arsenic), all of them held by mental associations and three related radiating lines that emanate from the centre of the painting. The varied images are suspended in a field of Mellow Yellow tones: for Whiteley head-turning yellow was the quintessential colour of America and he saw it beaming out everywhere: in Kodak film packets, in New York’s taxis, in its mustards, school buses, signage, sanitation trucks and in Con Edison gas pipe laying shelters.4 Certainly, Whiteley used the colour yellow before and since his time in Manhattan, but nowhere does his use possess the locational aptness and glowing optical intensity as encountered in his Gauguin of 1968.

Despite its seemingly complex visual energy and the boldness of its forms the large painting has a tableau-like equilibrium. Its palpable sense of central compositional calmness results from a mid-point optical balance: the frenetic, freely brushed colouristic biomorphism of the Tree of Knowledge on the left is counterbalanced by the fleshy, smooth and almost monochromatic contours of the female figure on the right. The collaged 1891 photographic image of Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) sits throne-like as a central visual hinge in this splayed-out pictorial field, the whole of which is presented to the viewer on an enormous cheese platter-like or painting palette shaped panel.

Viewed in this way the painting acts as a montage of Gauguin’s imagined musings. Its melange of flowing forms spill from Whiteley’s empathetic identification with the tribulations of the French artist who acts as a stand-in intermediary for his own personal misgivings and artistic anxieties. Despite popular opinion, great talent is a considerable burden and Whiteley, during this turbulent period, clearly and sympathetically identified with those luminaries before him who had, like him, stumbled during their own paths to greatness – Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Gauguin, Rembrandt, Bacon, Behan, Dylan and Van Gogh. Moreover, there is much to suggest that Whiteley’s Gauguin is the conceptual precursor to the seductive colours and swarm of images that surround his icon-like portrayals in his Portrait of Baudelaire of 1970 and Portrait of Arthur Rimbaud

of 1971.

During this time Whiteley read about the maladaptive life of Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) – an artist whose movingly unfathomable paintings he much admired after seeing them in London (an image of Gauguin’s journal Noa Noa occupies the centre of the painting).5

Gauguin, like Whiteley, was a driven man. However, he was constantly crippled with pain and suffered from many ailments, not the least of which was syphilis. On 30 December 1897, in deep despair about his failing health, bitter disappointment regarding the publication of his journal and severe depression after receiving news of the death of his nineteen-year old daughter Aline, Gauguin attempted to end his life through suicide. He limped up (he had a badly ulcerated leg) to a nearby mountaintop and took a large dose of arsenic (he had a supply for pain relief) only to have his body react and vomit it up. He awoke, went back to finish his magnum opus painting (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? of 1898) and, chastened by his brush with death, continued to live for another six years - all this in what he thought was an artistic Eden.6

One can appreciate that, for Whiteley, the heart-wrenching details of Gauguin’s life must have seeped in like the wafting lyrics of a sad, yet beautiful, distantly sung aria. There was a certain confluence. Here he was in New York, an artistic Eden of another sort, wracked by a severe disappointment with what the promise of American society had proffered up. Venality, the Vietnam War, violence and the vehemence of sit-ins, and demonstrations – all seemed to point to a deep and depressing fissure in Post-Kennedy American culture.

However, it is important to stress that there is no hint of suicidal despair in Whiteley’s life or art at the time – this is not a symptomatic or cathartic painting. Its original impulse is simple: the tragic story of the voluptuary Gauguin must have had a sobering, even piercing, quality – one that penetrated deeply and prompted the creation of his Gauguin of 1968. The image of Gauguin sits centre stage in the painting, but there is little doubt that Whiteley is its eye in the middle of its storm of mentally summoned-up images. As a consequence, the painting reveals more about the artist than about the subject. After all, what we see depicted in the present painting is not an event in Gauguin’s life, but one in Whiteley’s.

Considered and understood in this way, the underlying power of Whiteley’s painting Gauguin of 1968 rests in its meditational identification with the French artist. That is, it arose from a process of what might, if it can be forgiven, be called a type of transpositional empathy.

By way of explanation, Gauguin’s life became the container into which Whiteley poured his own content. This is not new in Whiteley’s art. He had done a similar thing in his emotion-laden and memorable London-based Christie Series, with its nods of acknowledgement to the influence of the justly admired English artist Francis Bacon (1909-1992). However, what is different, utterly new in fact, in Whiteley’s Gauguin is its psycho-literary source in Gauguin’s book Noa Noa and his alter-ego personalised adoption of its content for his own analogical use. This subtle ideational shift is the deeper source of the painting’s “double-punch” visual impact.

Nonetheless, it must be admitted that Whiteley’s content is not altogether clear. Despite this, one may safely surmise that the painting Gauguin sublimates deeper urges and pictorialises quandaries and dilemmas within the artist himself. What is being posed in this impressive painting is a some sort of deeply private choice of direction: between the seeking of the pleasure of knowledge on the left and the hedonistic pleasure of carnality on the right - with the uppermost out-of-reach phial of arsenic acting as an analogy of a futile solution.

What one sees in Whiteley’s Gauguin is a seismographic mood picture that displays his own twin gazed vacillations. The whole painting presents as an amalgam of being lost in and to the pleasures of the body and being lost in and to the fecundity of Nature – just as may be amply seen in the suggestively lush panoply of Gauguin’s paintings.

One feels the presence of a personal parable – one based upon the weighing up of possibilities. However, like many parables that attempt to show a truth, an action and a result, precise meanings and purpose often remain unclear – even for Whiteley the issues are unresolved. For instance, the white page in the centre of the painting remains blank as though the artist himself is equivocal – though one may note that the head of Gauguin appears to nod in the direction of the female body to the right as if his eyes were averted from the Tree of Knowledge in the left-half section of

the painting.7

Another revealing connection appears in this left section. The large carved figure to the left of the Gauguin image in the preparatory drawing for the present painting is almost certainly that of Oviri (Savage in Tahitian) of 1894 by Gauguin (originally intended for his grave and now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris) that, according to the world authority John Richardson, Pablo Picasso thought impressive when he saw it in 1906. In Whiteley’s painting this tribal figure is modified and depicted with its arms raised surprisingly like that found in the central figure in Picasso’s famous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon) of 1907 – the painting (purchased in 1937) exists in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, just thirty short Manhattan blocks uptown from Whiteley’s penthouse apartment. The inference that Whiteley modified his tribal figure after seeing Picasso’s masterpiece at MOMA is

almost inescapable.

Essentially, Whiteley’s painting Gauguin is marked by a giving-over to sensation – a word that Whiteley used more often than most. Whiteley has continually described his reactions to things in terms of sensate input – of personal perceptions, subjective effects and physical responses, rather than “meanings”, literary content, “expressions”, “impressions” and the like. For Whiteley, art was always a felt thing – that is, it was much more visceral. There was something of the antenna about his detection of incoming signals.

Little wonder that the painting’s compacted affective strength and its wide-ranging emotional compass are so breathtaking in their sweep and gravitating in their suggestive power. The remarkable thing is that the painting prompts and then unpacks in the viewer a type of emotional transport. The painting’s entwined forms, loose applications of seductive colours and its sweeping linear flows entice the viewer into an amalgamated Gauguin/Whiteley inner world of roaming associations and subjective connections.8 Such is the associative power of this striking painting that Whiteley’s Gauguin might just as easily be called “Alter-ego Portrait of the Artist in a Metropolis” if only to nail down its interleaved layers of personalised content and its stand-in revelation of self.

Whiteley’s Gauguin is a type of euphoria in paint – a turbo-charged Romanticism – a form of communion with the self that seeks contact with something larger than the self.

This is the hidden crux of its visually loaded-up balance of emotional associations.

Whiteley’s stay in New York occurred during a pivotal five-year blossoming phase in the middle of his short life – a period that lasted from 1966 to 1970. His painting Gauguin of 1968 was created in the exact mid-point of that crucial period. In this sense, but not only in this sense, it is a centrally important and highly significant painting in Brett Whiteley’s stellar life.9

Looked at in total, for all these compelling reasons, Brett Whiteley’s Gauguinof 1968, with its brilliantly sublimated subset of issues, is a highly distinctive and truly remarkabletour de force- all this from a twenty-nine year old!

Associate Professor Ken Wach

Dip. Art; T.T.T.C.; Fellowship RMIT; MA; PhD

Emeritus Principal Research Fellow and Head,

School of Creative Arts

The University of Melbourne

Footnotes

1. See: Miller, A., “The Chelsea Effect”, Granta 78: Bad Company, 15 June 2002, u.p. Miller offers up the following reason for his tenancy (Room 614) at the Chelsea Hotel: “I decided to move to the Chelsea in 1960 for the privacy I was promised. It seemed a wonderfully out-of-the-way place, nearly a slum, where nobody would be likely to be looking for me. It was soon after Marilyn and I parted, and some of the press were still occasionally tracking me, looking for the dirt in a half-hearted way”. Arthur Miller (1915-2005) is the author of Death of a Salesman and The Crucible and his last play is Mr. Peter’s Connection (1998). Miller was married to Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962) from June 29 1956 to January 20 1961. The twelve-storey Chelsea Hotel (when it was built in 1883 it was New York’s tallest building) was located at 222 West 23rd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues in Lower Manhattan, New York – it was sold ($81 million) in August 2001 and is currently undergoing extensive renovations; it is due to reopen in 2015.

2. Whiteley moved in, with his wife (Wendy (1941-) and daughter (Arkie (1964-2001), to The Chelsea Hotel in 1967 and left in haste and disappointment in 1969, leaving the present painting as part payment of his hotel rent.

3. Whiteley had met Robert Rauschenberg in London and visited James Rosenquist in his studio in New York – he was well acquainted with their works.

4. Yellow currently has fifty-five recognised shades – Mellow Yellow was invented in 1948 and forms one of the accepted colours in the Piochere Colour System. Coincidently, Mellow Yellow, the song by Donovan, was extremely popular in 1966/1967 (No. 2 on US Billboard/No. 1 Canada/No. 8 in the UK) – the colour yellow also developed vaguely countercultural associations. It is oddly interesting that the Donovan song refrain “Quite Rightly” sounds surprisingly like “Quite Whiteley”.

5. Gauguin started his journal Nao Noa while in Tahiti (1891-1893); the words of the title refer to the heady fragrance of the island’s gardenia-scented women. Gauguin’s book was written to accompany his exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris and later it was given to the poet Charles Morice, who sold it in 1908 to the publisher Edmond Sagot – it then remained unpublished and was the source of constant disagreements until well after Gauguin’s death when negotiations were settled between the publisher George Cris and Gauguin’s wife Mette in 1920 – the book was eventually published in 1924 and illustrated with twenty-four woodcuts by Georges-Daniel de Monfried.

6. For excellent overviews of Gauguin’s life see: Rewald, J., Paul Gauguin, New York, Abrams, 1970 and Sweetman, D., Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, New York, Hodder & Stoughton, 1995. See also: Gauguin, P., Noa Noa: The Tahitian Journal, New York, Dover, 1985.

7. This observation is supported by a clear arrowed line connecting the same collaged image of Gauguin of 1891 and that of a young Tahitian female (later omitted from the painting) in the preparatory drawing for the painting: see: Study for Gauguin, 1968, pencil, ink, collage and adhesive tape on paper, 1968, 35.3 x 55.7 cm, private collection, Sydney, illus. in Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley, Art and Life, Sydney, Thames and Hudson and The Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1995, fig. 37, p. 46.

On the role and significance of the Oviri figure of 1894 by Gauguin see: Sweetman, D., Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, New York, Hodder & Stoughton, 1995, p. 562-563 and Richardson, J., A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1991, p. 459. See also: Landy, B., “The Meaning of Gauguin’s Oviri Ceramic”, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 109, no. 769, April 1967, p. 242, 244-246 and Taylor, S., “Oviri: Gauguin’s Savage Woman”, Journal of Art History, vol. 62, Issue 3/4, 1993, p. 197-220.

The Tree of Knowledge is a recurrent theme in Gauguin’s paintings – see Cachin, F., Gauguin: The Quest for Paradise, New York, Abrams, 1992, passim.

8. Specific primary sources in the form of letters and notes that might fill out or underscore these observations are currently unavailable.

9. The painting draws attention in the two most influential publications on Whiteley’s art: McGrath, S., Brett Whiteley, Sydney, Bay Books, 1979, pp. 86, 87 and Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley, Art and Life, Sydney, Thames and Hudson and The Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1995,

fig. 37, p. 46.

Literature

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2007.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 9 Shades of Whiteley, Regional Tour, (Gold Coast Regional Art Gallery, Lismore Regional Gallery, New England Regional Art Museum, Maitland Regional Art Gallery, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery), 12 July 2008 to 23 August 2009, Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2008.

“Brett Whiteley”, Obituary, The Times, London, 18 June 1992.

Gray, R., “ A Few Takes on Brett Whiteley” Art and Australia, vol 24, no. 2, Summer 1986.

Hawley, J., Encounters with Australian Artists, St. Lucia, University of Queensland Press, 1993.

Heathcote, C., “Whiteley: the pleasure king of modern art”, The Age, Melbourne, Thursday 18 June 1992, p. 14.

Hilton, M.; Blundell, G., Whiteley: An Unauthorised Life, Sydney, Pan Macmillan, 1996.

Hughes, R., The Art of Australia, Melbourne, Pelican, 1970.

McCulloch, A., “Letter from Australia”, Art International, October, 1970.

McGrath, S., Brett Whiteley, Sydney, Bay Books, 1979.

Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley, Art and Life, Sydney, Thames and Hudson and The Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1995.

Pearce, B.; Whiteley, W., Brett Whiteley: Connections, Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Healesville, 2011.

Richardson, J., A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1991

Sweetman, D., Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, New York, Hodder & Stoughton, 1995.

Smith, B.; Smith, T., Australian Painting 1788-90, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: A Sensual Line, Melbourne, Macmillan, 2010.

Thomas, D., Outlines of Australian Art: The Joseph Brown Collection, South Melbourne, Macmillan, 1989.

Wilson, G., Rivers and Rocks, Arthur Boyd and Brett Whiteley, West Cambewarra, Bundanon Trust, 2001.